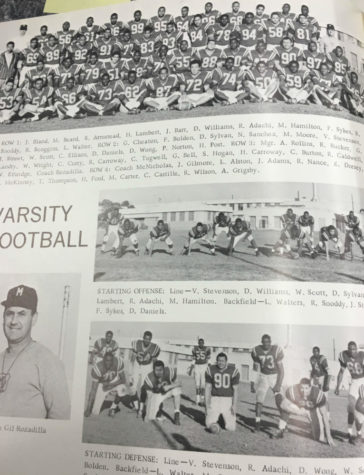

Football: Then and Now

April 28, 2017

It’s 1965. Manual Arts High School is preparing for battle against Lincoln. With 13 city championships already under their belt, the football team knew how to win. The varsity players started every game with the same regiment. Pads, purple and silver jerseys and a pep-talk. The team was feared. The team was respected. Center Homer Post was usually the biggest player on the field, and his opponents didn’t know how to stop him. Ronnie Ray Smith could not be caught. He was known to be the fastest player in the city. And then there was Miguel Roura. Standing no taller than 5’5, Miguel didn’t get the opportunity to play much. He wasn’t the bulkiest player and he didn’t have the fastest legs, but he did have the biggest heart.

Miguel loved the atmosphere that surrounded the football team. Although he rarely got an opportunity to play at Manual Arts, he admired the little things like the uniforms, the practice, and even watching his friends play. Miguel was very active. If he was not playing football he was at his sanctuary, Toberman Park, playing baseball, table tennis, and basketball. “ I never got picked when basketball teams were chosen. I was short, chubby and not very quick, but when baseball season came around and Mr. Lacefield started hitting ground balls for us to field, he saw I had skill,” said Roura. Miguel was living the good life. But just outside of the school walls was a community in conflict. In 1964, Miguel’s junior year, the United States enacted the Civil Rights Act, outlawing discrimination based on race, religion, sex, color or national origin. The following year, 10 miles South of campus, the Watts Riots took place, amplifying the racial tensions between police and the black community. This led to a period of “white flight,” causing the South Los Angeles community to become predominantly Latino and black. The period was known for social activism and minority empowerment. Gang violence evolved into organized movements led by the Black Panthers and the Brown Berets. Miguel was affected by these changes.

As a Chicano boy, moving from school to school, he faced many challenges. Miguel was going to Manual Arts High School which was surrounded by a predominantly African American community. “I was frightened at first when I came to Manual Arts High School because my friends at Lincoln High School were saying be careful. ‘They are predominantly black, you know,’ they would tell me.” Around the community there was a lot of gang violence and conflict between the police and the various gangs that were just picking up momentum; as a result Miguel felt worried. He was afraid of what he heard from people. But when he was playing football, none of that mattered. There was no black or white, no us and them. The team was united even though the community was starting to fall apart.

***

It’s September 3, 2016. Demani Nichols has a twisted ankle and a bruise the size of a basketball on his hip from last week’s game. The players are drenched in sweat. They try to catch their breath between the plays. The coach is calling a play, but all the players can hear is the home crowd cheering and the sound of their heart beat echoing in their ears. On the field are the All City football team stars Darion Turner and Quadir Dean. Demani is not a star player but he has given his all in every game this season. To most, this may sound like an average football game on a Friday night, but for players like Demani and many who live in South Central, Friday nights are sacred.

With gang violence and drugs around the school community, many kids use football as an escape. For those four quarters, the players on the team don’t have to worry about academics, what’s going on in the community or at home. “When I first started playing football in my junior year, I didn’t know what I wanted to do or where I was going,” said Damani. He was lost, but with the help of his Coach De’andre Nichols, he made a plan. “I wasn’t familiar with someone that stern that wasn’t my mother or my father,” explained Demani. “Coach Nichols preached like a leader and he molded us into men.” Without football many of the players would be victims of the hard realities that surround the school.

With the city’s history littered with gang violence, drugs, and racial tension, Coach Nichols feared the boys would give up and succumb to this unrelenting narrative. He did not want his players to become another statistic. Coach Nichols didn’t give up on the players. He would schedule one meeting that he knew would motivate the team and get the community’s support. Coach Nichols decided to gather the community and ask if they would help fundraise for the team. The community came together as a cohesive unit and raised almost $10,000. “That year, our coaching staff filled our heads up with a mindset of winning,” said Demani. “At first we were pessimistic due to our past decades’ history. Winning just didn’t seem realistic, but we bought into what he told us. We trusted him.”

Although the team didn’t have much faith, the coaching staff did, and slowly but surely it translated to the players. Eventually, through all their hard work, the team would begin winning. With winning came an increase in community support. “It was weird, I had never seen a crowd so large, but when we started winning the community came out and supported,” said Damani. “It made us play harder knowing the games meant something to other people.” Every Friday, crowds gathered by the dozens to come and watch Manual Arts win a game, something that hadn’t happened in years. “Parents and people from all over helped fundraise and the support got so crazy we actually sold out seats at homecoming and had to reserve seating for the other team’s supporters. We felt the love for the first time ever.” Manual Arts would go on to make the playoffs for the first time in a long time. Despite the community having a negative perception of the school, the team’s success showed what a few people can do when they care.

While it may seem like a simple game of football, the impact the game has had on the community over the course of five decades is astonishing. All the tears, sighs, laughter, and cheering all came to an end with the season. Despite the fact that Manual Arts High School may never get another championship moment, the community’s support made each individual on the team feel like a champion. Players, coaches, and referees are part of the game, but the community is just as significant. For that one season, the men forgot about their troubles, put their pain to the side and wore their purple uniforms proudly.

A lot has changed since Miguel’s time on the field in the 1960s. Despite coming from two different worlds, Demani and Miguel would face similar adversities growing up. Both used the game as escape from the community issues around them. Five decades seems like a long time and the community looks very different than it did fifty years ago, but the game of football hasn’t changed much and that is what the players hold on to.

Will Etheridge, class of Summer 1966 • Aug 11, 2017 at 10:50 am

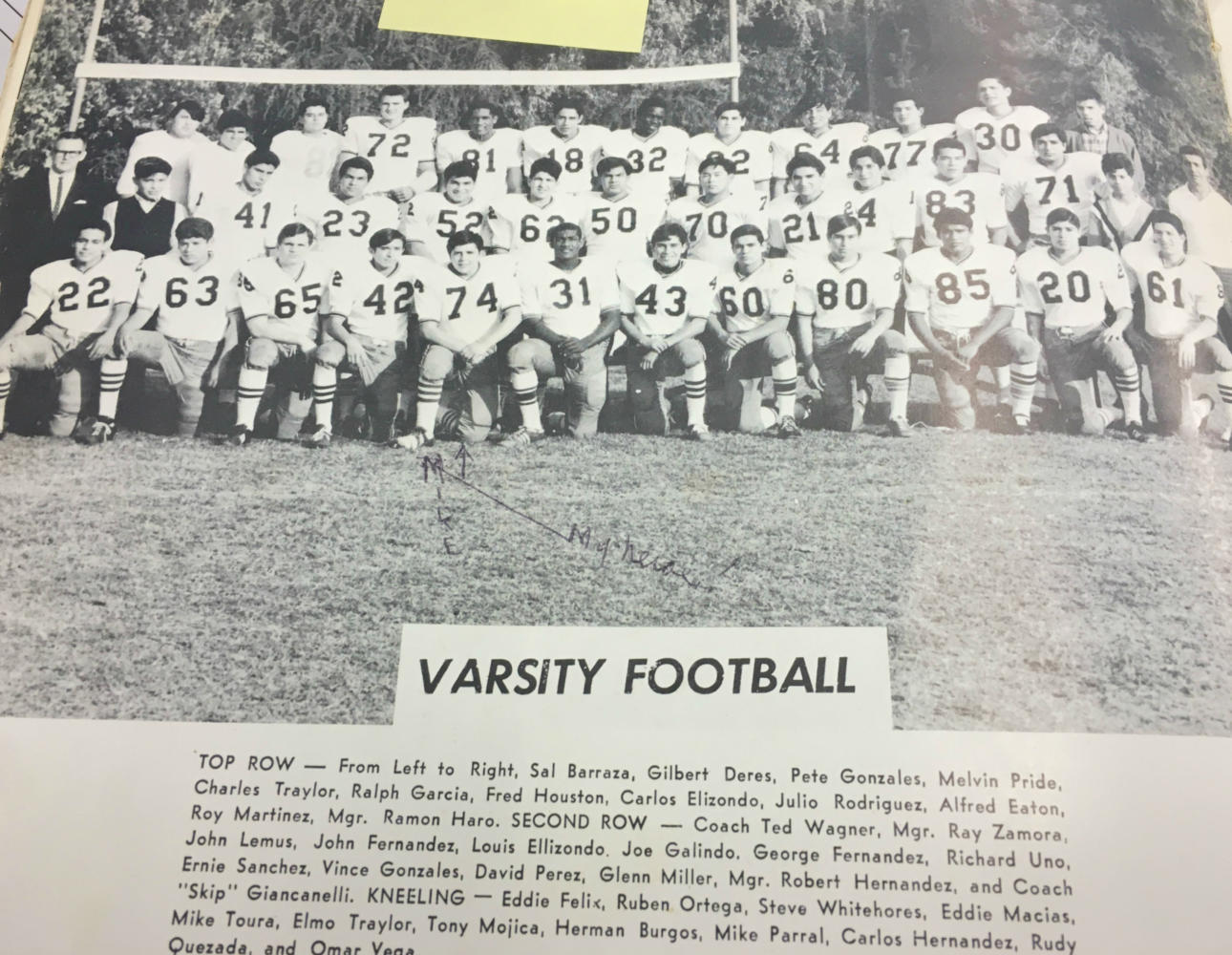

I’m sorry, but after reading this story in the TOILERTIMES I have to offer a few corrections. The photo slugged “Varsity Football” is Lincoln’s 1962 team. Manual Arts met the Tigers in the 2nd round of the playoffs that year. The teams played to a 0-0 tie. Manual advanced to the finals on something called “the Costello Rule” meaning the Toilers had more 1st. downs inside the opponents 20 yard line. We went on to beat Birmingham HS 21-0 and win the City Championship with players like: Clayton Calhoun, Ray Cahill, Harry Wells, Carlton Kelly, Manuel Juarez and most important Coach Jim Blewett. Lincoln was small in size but big in heart they had the Kucinas (sp) brothers.

The second team photo is the 1964 Southern League Champs. Homer Post (#85) played tackle and end on that team not center. Our center and middle-linebacker was Harry Lambert (#73) an All-City player. Also on that team was future USC and Oakland Raiders defensive tackle Willard Scott (#88) All-City and Southern League Player of the Year.

Perhaps a better example of racial harmony would have been: Nick Sanchez (#51.) Nick lived on a cross street near Exposition Bl. and near the Coliseum in “jet black” south-central LA at the time. Nick was our 2nd string quarterback and he took beatings in practice everyday, running the “red team” and our opponents plays. Nick was not all that talented but he always showed-up. He is the father of Mark Sanchez (USC, Jets and other pro teams)

As for “white flight” it had its’ start way before the 1965 Watts riots. Manual’s student body was and still is reflective of the racial changes the school and south-central LA has gone through. The school was predominately white until the late 50’s. In the early 60’s the school became predominately black and now it is predominately Latino.

I know these things because ALL our coaches went to Manual and they would tell us stories about the people, the legends that played before us. People like: Tom Fears, Jon Arnett and a Spaniard-tough-as-nails coach named: Nebb Elduayuan (sp) as well as many, many others. I am (#81)standing next to Coach Gil Rozadilla in the 1964 team picture.

I was pleasantly pleased with the progress and success of last year’s team. And, I hope with all my heart and soul that we can return to the days of glory this coming 2017 season. Purple and Grey, Forever and a Day. Sincerely, Will Etheridge Class of Summer 66. It Can Be Done!